I, like most people, tend to think of video games as art by default.

But unlike a lot of people, I don’t like the idea of numerically judging art, even when it is a game. For instance, no one’s going to go into a museum and point at art installations and give them star ratings. Not without missing the point entirely, at least. I think it’s a lot more meaningful, when looking at games as art, to instead analyze what it’s trying to do and what it’s trying to say.

But then, unavoidably, some games are quite thoroughly products. Yearly sports games are an example: since they have standards and long-held audience expectations, and on top of that are with made more or less no artistic choices compared to the previous year’s installment, I believe they can comfortably be judged as products. Games that emulate other games- virtual editions of board games for instance- also become products by virtue of their ability to reproduce what you’re using it as a proxy to provide.

In general, the line between art and product is quite nebulous, but I do think often enough, it leans more towards one way or the other. I personally break things up into two categories- design by committee, representing games as product, and design by auteur, representing games as art. I’ll break down these classifications and go into a bit of detail about what I think makes games lean more towards one or the other.

Design by Committee:

“Committee” games are made by generally large-to-enormous teams with lots of oversight and concerns about how broad their consumption can be. These are often games commandeered by companies that care about their shareholders and are afraid of taking risks, upsetting audiences or review scores.

For instance, Mobius Final Fantasy’s original design for Wol was much more revealing, but was toned down due to audience feedback. To me, this is the kind of thing that indicates more of a “committee” approach where an artist’s intent is tempered by expectations of an audience and trepidation about doing anything risky.

Some games have access to an obscene amount of resources in the ballpark of many millions, and these games overwhelmingly skew towards the “committee” side of things. Let’s imagine, for a moment, a franchise that was the “largest franchise in the world.” Something highly marketable that proved to be the biggest cash cow ever made in all of video games, releasing once every year or two. This leans towards “committee,” clearly.

Let’s say that one year, our hypothetical franchise hikes up the price while at the same time taking away features that came to be standardized. I believe this can be readily criticized, because it’s a multi-billion dollar generating corporate machine that’s trying to make people pay more for less features that had become standard.

Now let’s imagine a yearly Madden game suddenly doubled in price and yet took away the ability to play every team except for the New York Giants. I don’t think anyone would fail to see how audience reaction would be not only understandably, but perhaps justifiably, incensed.

However, with the murky subject of games as art vs. games as product, and the hostility between the debating camps, sometimes the toxic parts of fan anger effectively serve as a shield for corporations delivering a cheaper “committee” product. The people who don’t care about the franchise’s step back look down upon the people who do, trivializing the issue by waving their hand and saying “it’s just games,” blame audience expectations as a factor making crunch culture worse, or painting the entire viewpoint of having franchise expectations as toxic because of a minority of fans are stepping out of line- which is something that will occur with any group of people once it is large enough.

I feel “committee” games, since they’re providing a regular service or experience, are reasonably beholden to valuation of their product due to their intrinsically more crass nature. I don’t want to sound soulless here, so let me go ahead and say I’m not a fan of capitalism, and that it can be pointed to as the root cause of many of committee games’ shortcomings.

Fans stepping out of line and becoming toxic in their reactions to the shortcomings of committee games is by no means a good thing, but it also should not be ignored that the purchase of poorly made committee games strengthens corporations and emboldens them to continue to squeeze more money out of working class gamers for less quality on their part.

In the end, “committee” games are designed to be enjoyed through consumption of content that has been made to catch peoples’ interest and not step on any toes.

Design by Auteur:

“Auteur” games are usually made by single authors or small teams, or otherwise have very strong authorial or directorial voices powerfully featured in the work. These are typically games that have a distinct vision and pointed intent. I will virtually always consider indie games “auteur.”

Larger games can definitely be “auteur” works. As a few examples of these sorts of video games on a larger scale, I would list Hideo Kojima, Suda51 and SWERY as prominent “auteur” style directors. Team Silent and genDESIGN (formerly Team Ico) are some teams that produce games with a strong “auteur” feel.

This is not to discredit the many people working alongside the aforementioned directors and teams as valid contributors to the project, which they absolutely were, and the projects would not exist without their help. This is simply a framework for gauging what works by larger studios may yet qualify as “auteur.”

I believe by nature of trying to give you a certain feeling or present a certain idea that “auteur” games are to be judged on a different metric than “committee” games. These are experimental games that aren’t trying to have perfectly executed mechanics, or perhaps they’re even subverting mechanics in ways that will risk giving people a knee-jerk reaction of the game being poorly made because of it. They might slow down for a second to tell you something nonsensical in hopes of establishing a mood. They might troll you or be “difficult art” to consume, not as in a video game sense of requiring a high level of skill, but as in you must engage with it and try to understand it on its own level.

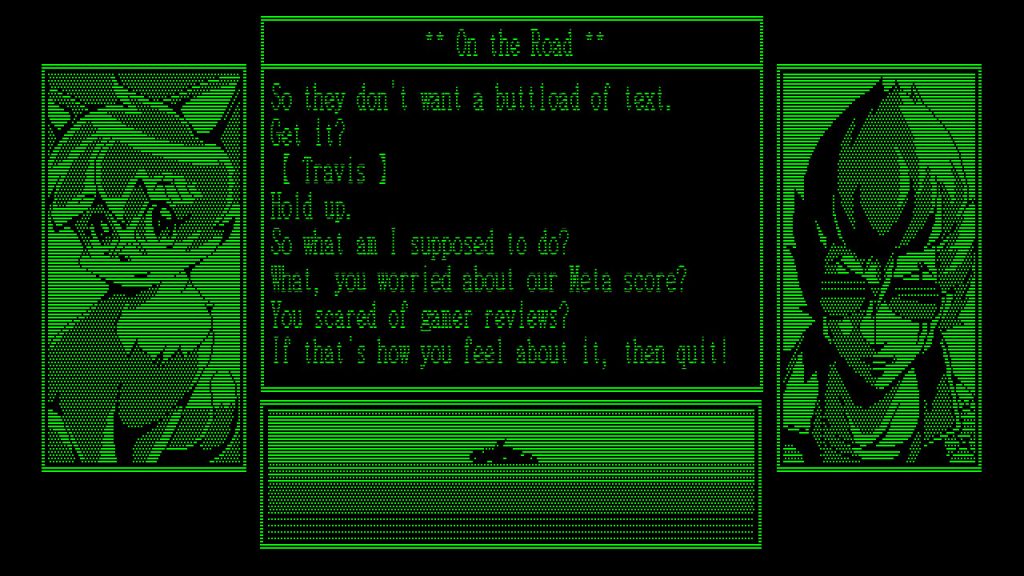

Grasshopper Manufacture’s 2007 Wii title No More Heroes featured a notoriously critically reviled open world. At the time, I more or less understood why this open world segment was thought of so critically: to me, and many others, it was simply an intermission between accepting jobs and carrying them out, simply a place where you hopped on your bike and moved to the next quest marker. You made a lot of trips in and out of this world as you grinded enough money to either access the game’s next level or buy a weapon or stat upgrade if you so desired.

The grinding, another aspect of the game people took issue with, was not particularly excessive, mind you, and featured a healthy variety of ways to carry it out. Longplays of No More Heroes range from 6.5 to 8.5 hours. For the game’s wealth of content, it was really not an especially padded game- but for those who were only there for the boss fights, trying to quickly consume the game without appreciation for the part-time jobs or the goodies hidden in the open world, it was an annoyance.

However, there were plenty of collectables to be found- you could find a ton of shirts to wear, as well as 49 “Lovikov Balls” that can be traded in for bonuses at a store you might not even find. These details and whatever it might have done for pacing, the texture of the game, or what vibes it was going for were overlooked because it wasn’t engaged with or pondered so much as interpreted as an obstacle in the way of rapid consumption.

In a “committee”-minded move, perhaps at the behest of publisher Marvelous Entertainment, No More Heroes II made numerous changes in response to the critical reception of its forebear, most significantly axing the open world and replacing it with a text menu where you simply chose where to go. You no longer walked, drove, or sprinted with a ridiculously large dust cloud down to the fashion shop, you just pick an option and you’re simply there.

To me, the reception of No More Heroes represents the difficult road that “auteur” games walk when they are engaged with as though they are a product to be consumed instead of a piece of art to be experienced.

In the end, “auteur” games are designed to be enjoyed through appreciation of art which aims to demonstrate a concept, provoke an emotion or interestingly play with tropes and mechanics.

My Review Criteria for “Committee” vs. “Auteur” Games

Of course, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to reviewing media, but here’s an idea of how mine works. I use Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s concepts of “paranoid reading” and “reparative reading.”

I tend to approach “committee” games as a paranoid reader. These are products that often come from multimillion dollar corporations which are often afraid to do anything too risky or champion progressive rights. If they want my money, they have to make it past my skepticism and deliver a truly quality product. With “committee” games I take notice of what it’s failing to deliver on that its competitors or previous installments do.

I tend to approach “auteur” games as a reparative reader. These are pieces of art that come from smaller companies and take risks to make a point or share some interesting vibes, and more often include themes of progressivism and representation. Overall, it is often clear they do not have the budget of “committee” games, being more rough around the edges and experimental. In narrative they are sometimes imperfect, as the limited voice and direction can lead to displays of ignorance. But such is the nature of art- many famous artists through the ages held ignorant beliefs, but their work continues to be admired for what it is. With “auteur” games I think about what unique aspects they’re bringing to the table, not what I would expect them to do as though they were a “committee” game.

A Quick Note on Capitalism Sucking

In poor countries, the price of a game can be prohibitively expensive. For poor people in these countries especially, games must be judged as products before art, because they’re competing with spending that money on survival instead. This analysis and outlook on game evaluation comes from a relatively privileged position of lower-class America, with enough money to spare for frivolities such as artistic video games. It is not meant to invalidate the discretion taken by those who have so little money that purchase decisions are made with paramount importance.

BONUS – Design by Hobbyist:

All of the aforementioned was written in regards to games that you pay for. But there of course is another type of game, close to the “auteur-” the hobbyist. This might be ROM hacking, fangames, or small free games in general. This is not intended to be reductive or to discredit a hobbyist’s role as being an auteur themselves, far from it! The way I approach what I consider to be “hobbyist” games is very similar to “auteur” games, except with even more leeway, because, you know– it’s a joyful thing that was given to me for free. That’s wonderful. I’ve loved plenty of “hobbyist” games much more than “committee” games, for the record.

Hobbyists, in spite of this, can have an unfortunate amount of hostility within their ranks in some circles. For instance, Super Mario Bros. and Mega Man level creation will often be passionately criticized as though they, too, were commercial products. I think this kind of reaction is to be avoided- to praise the best, but also to be kind to the worst, lending them nothing but guidance to try and lift up their craft without compromising their individual voice and self-expression.

With hobbyists, there’s a place for criticism for the sake of the craft, but I think it should be centered on positives rather than negatives. The kindest approach is for the worst to be given gentle suggestions and guidance rather than derision. “This sucks because it’s ugly and there’s too much instant death” is much less kind to fellow humans than “I wish it was easier, and maybe you could practice a little on making your levels look more fancy.”

Bun